BLUF: In Northern Virginia, new GovCon firms don’t lose because they can’t deliver; they lose because evaluators can’t quickly see proof. From day one, build a mission-focused website (not a cookie-cutter GoDaddy/Wix template), spin up micro-niche landing pages for each target agency, and pair them with sharp, 508-ready capability docs optimized for AEO so contracting officers and primes find you, trust you, and act. Do this, and your top-10 startup hurdles: registrations, past performance, CMMC, pricing, vehicles, proposals, pipeline, cash flow, talent, and differentiation, become a process, not a brick wall.

Table of Contents

- What Is the RFP Process?

- How the Government RFP Process Really Works

- RFP Requirements That Decide Winners and Losers

- Understanding the RFP Contract Lifecycle

- Where Government Buyers Find U.S. Defense Contractors

- Multi-Industry Defense Contractors and Why They Matter

- The Role of Government Contractor Website Development

- SDVOSB Teaming Agreements Explained

- How U.S. Military Contractors Position for Long-Term Wins

- Common RFP Mistakes Contractors Make

- Final Takeaways for Defense and Government Contractors

As a former federal official turned contractor and digital strategist, I’ve spent decades navigating the Request for Proposals (RFP) process from both sides of the table. In that time, I’ve seen how U.S. defense contractors succeed (and struggle) in a multi-industry marketplace where technology, services, and manufacturing often intersect. In this comprehensive guide, I’m going to demystify the government RFP process and share firsthand insights on how defense and government contractors can position themselves to consistently win contracts.

Why listen to me? I’m Daniel Scott H., Founder of HILARTECH, LLC – a Service-Disabled Veteran-Owned Small Business (SDVOSB) and federal contracting web design firm. My background includes roles as a U.S. Navy Chief, FBI official, and DHS cybersecurity policy lead. I’ve been the guy reviewing proposals inside government agencies, and now I’m the one helping contractors present their best face to those agencies. This means I understand how the government RFP process works, which requirements determine winners and losers, and how factors such as multi-industry capabilities, teaming agreements, and a strong digital presence all contribute to long-term success.

In this report-style blog, I’ll cover everything from RFP basics and lifecycle to advanced tactics for U.S. military contractors. Each section is clearly labeled, so feel free to skip around or bookmark for later. You’ll also find actionable takeaways, internal resource links, and even suggestions for tools like an RFP checklist you can use to avoid common pitfalls. Let’s dive in.

1. What Is the RFP Process?

RFP stands for Request for Proposals, and it’s a formal process the government (and many private-sector organizations) uses to solicit detailed proposals for complex projects. In plain terms, an RFP is how government agencies ask contractors: “Here’s what we need – who can do this for us, and how will you do it (and at what cost)?”

Defining RFPs (Request for Proposals) in Government Contracting

In the government RFP process, an agency identifies a need and issues an RFP document outlining the project requirements, evaluation criteria, and submission guidelines. The RFP typically includes a Statement of Work (SOW) or Performance Work Statement (PWS) describing what the agency wants done, instructions on how contractors should format and submit their proposals, and the criteria by which the proposals will be judged. Contractors who believe they can fulfill the need then prepare detailed proposals explaining exactly how they will meet the requirements – including their technical approach, management plan, past experience, and pricing.

Why the Government Uses RFPs (Purpose and Objectives)

Once proposals are submitted, the agency evaluates them against the stated criteria and selects a winner (or winners). The goal is to award a contract to the contractor that provides the best solution and best value for the government, not always the cheapest, but the one that offers the optimal combination of quality and cost. This whole sequence – from RFP issuance to contract award and beyond – is often referred to as the RFP process or the federal procurement process. Securing federal contracts requires multiple stages, from needs identification through contract closeout.

RFP vs RFQ vs RFI: What’s the Difference?

It’s important to understand that an RFP differs from other solicitations. The government uses Requests for Quotation (RFQ) for simpler procurements (often lowest price bids) and Requests for Information (RFI) or Sources Sought notices to do market research before an RFP. But when it comes to substantial, complex, or high-value projects – especially common in Defense Department procurements – the RFP is the tool of choice. RFPs invite more than just a price; they invite a plan, a team, a demonstration of capability.

Key characteristics of the RFP process:

- Formal and Structured: The RFP process is governed by procurement regulations, such as the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). It’s meant to ensure transparency, fairness, and competition. That means every RFP comes with a strict format and deadlines that contractors must follow.

- Competitive: Typically, multiple companies will compete for the same RFP. It’s not unusual for a dozen or more defense contractors – from large primes to small specialized firms – to submit proposals on a single opportunity. This competitive aspect is why mastering the process is so crucial for contractors.

- Multi-Industry Scope: A single defense RFP can cut across several industries or disciplines – for example, a contract to develop a new military technology might require expertise in software development, cybersecurity, manufacturing, and training all at once. In today’s marketplace, “defense contracting” is inherently multi-industry. Contractors often need to either possess or team up for a broad range of capabilities to cover all aspects of an RFP.

For example, if the U.S. Air Force issues an RFP for a cybersecurity system upgrade, the lead requirement might be software development (tech industry), but the project could also involve telecommunications, cloud services, compliance (industry standards), end-user training, and ongoing maintenance (service industry). A contractor that has multi-industry capabilities – or partnerships across industries – will be better positioned to offer a comprehensive solution. We’ll dive more into “multi-industry defense contractors” in a later section, but suffice it to say, the ability to bridge multiple domains is increasingly an advantage in winning modern defense contracts.

Finally, it’s worth noting the stakes: Federal RFPs, especially in defense, can be multi-million or even billion-dollar contracts spanning years. Winning one can transform a business’s trajectory – and losing one can be a big setback. That’s why experienced government contractors treat the RFP response process as seriously as any core business operation.

Pro Tip: If you’re new to federal contracting, start by carefully reading a few sample RFPs on SAM.gov (System for Award Management). Look at the structure: typically Sections A through M in a DoD RFP, covering everything from the solicitation form, scope of work, instructions to offerors, and evaluation factors. Getting familiar with the anatomy of an RFP document will make the whole process less daunting.

Now that we’ve defined what the RFP process is in theory, let’s talk about how it really works in practice within government agencies.

2. How the Government RFP Process Really Works

On paper, the RFP process is straightforward: identify need → issue RFP → receive proposals → evaluate → award contract. In reality, government procurement is a complex dance of requirements, regulations, and human factors. Having been on the inside of federal agencies, I want to pull back the curtain a bit on how the government RFP process really works behind the scenes.

Step-by-Step Breakdown of the Federal RFP Cycle

First, understand that long before an RFP is released publicly, a lot has already happened internally:

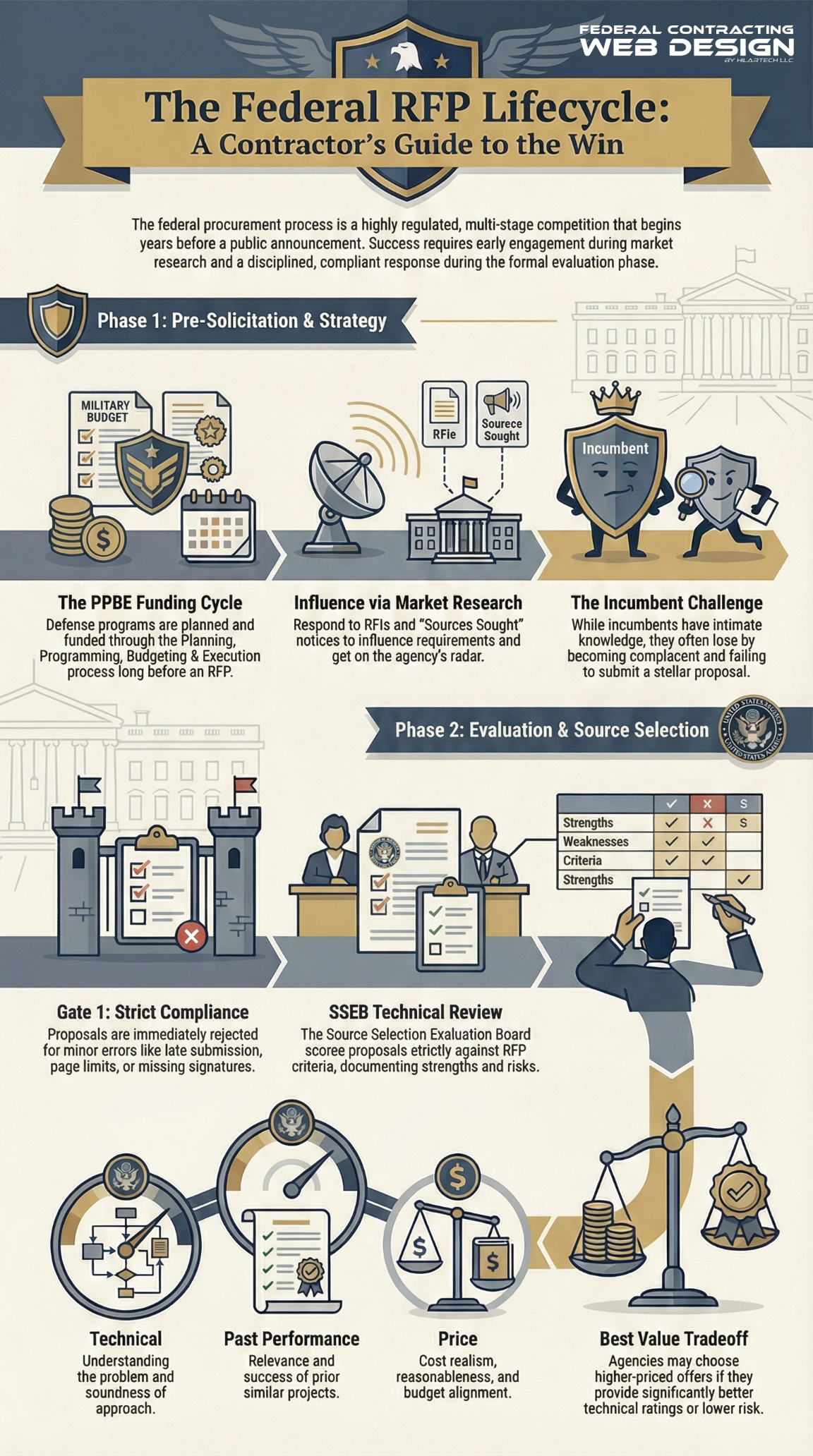

- Planning and Funding: An agency doesn’t just wake up and decide to issue an RFP. The process often begins months or years earlier, when program managers or military commands identify a need. They must justify the need and secure budget allocation. Especially in defense, programs are planned within the PPBE (Planning, Programming, Budgeting & Execution) process. By the time an RFP is issued, funding has usually been approved (or is pending congressional approval), and the scope is fairly well defined.

- Market Research & RFI Phase: Before writing an RFP, agencies frequently conduct market research. Contracting officers and small business specialists might search for available contractors in databases, issue RFIs (Requests for Information) or Sources Sought notices to gather information on industry capabilities, and even host Industry Days where interested companies can ask questions and learn about upcoming opportunities. If you see an RFI or draft RFP, take it seriously and respond – it’s a chance to influence the final RFP and get noticed by the buyer. Many contractors make the mistake of skipping this, but participating in pre-RFP market research can give you a leg up. I’ve personally seen cases where industry feedback led to adjustments to the requirements, favoring those who engaged early.

- Incumbents and Competition: Often, an RFP is for work that’s currently being done by someone else (an incumbent contractor). This means the incumbent likely has an advantage – they know the work intimately. However, they also have a track record that will be scrutinized (past performance), and they can’t become complacent. On the government side, I saw incumbents lose because they assumed they had it in the bag and didn’t submit a stellar proposal (a classic “assuming you’re a shoo-in” mistake). Meanwhile, a hungry competitor might outshine them with a fresh approach. Bottom line: the government tries to give everyone a fair shot, but context matters. Incumbent or not, never assume a win – earn it with a great proposal.

Now, inside the government, once proposals come in, here’s what happens:

- Compliance Check (Gate 1): The very first pass is often a compliance screening. The contracting officer’s staff will check: Did you submit on time? Did you follow the formatting instructions (page limits, font size, required forms)? Did you sign all required sections (like the SF-33 form or amendments)? If you miss any mandatory RFP requirements, your proposal could be rejected without even reaching evaluation. This is zero-tolerance stuff. I’ve sat on source selection teams where we had to discard proposals for being late by a few minutes or forgetting a minor form – painful for the bidder, but rules are rules.

- Technical Evaluation: The agency assembles a Source Selection Evaluation Board (SSEB) or a technical evaluation team. These are subject matter experts who will read your Technical Proposal (and sometimes Past Performance and Management sections, depending on how it’s structured). They score each section against the evaluation factors stated in the RFP. For example, if Factor 1 is Technical Approach, they might have subfactors with point values or adjectival ratings (e.g., Outstanding, Good, Acceptable, etc.). Crucially, they can only evaluate based on the criteria in the RFP and the content of your proposal – nothing else. They will document strengths, weaknesses, deficiencies, and risks for each proposal. If you fail to address a requirement, that’s a deficiency. If you propose something above and beyond, that might be noted as a strength.

- Past Performance Evaluation: Another team might separately review Past Performance references (sometimes the technical team does it). They look at your past contracts – how relevant they are to this work, and how well you performed (using CPARS ratings or reference checks). Past performance is a key indicator of future success. If you have no past performance, the FAR says you get a “neutral” rating (shouldn’t be penalized), but let’s be honest: in practice it can still make agencies nervous if one bidder has stellar relevant projects and you have none. This is why new contractors often team with more experienced ones (so they can cite the team’s collective past performance).

- Cost/Price Evaluation: Meanwhile, the contracting officer and perhaps pricing analysts will review the Price Proposal. They check for completeness, whether you’ve accounted for all tasks, and evaluate cost realism (especially for cost-reimbursable contracts). If it’s a fixed-price contract, they’ll compare prices among bidders for reasonableness. If the RFP is Lowest Price Technically Acceptable (LPTA), they will likely first eliminate any proposal that’s not technically acceptable, then simply pick the lowest priced among the acceptable ones. If it’s a Best Value Tradeoff, then they will weigh how much better a higher-priced proposal is versus its extra cost.

- Source Selection: The Source Selection Authority (often a senior official) receives the evaluation reports and comparative analysis. In a best-value RFP, they might choose a higher-priced offer if it has significantly better technical ratings or lower risk – but they must justify that decision in writing. If two proposals are technically equal, price can become the tiebreaker. There is often a meeting where the evaluation board presents findings, and selection is made. The government is meticulous here because a flawed source selection can lead to a bid protest by a losing bidder. (Protests are common in defense contracting – essentially a legal challenge to the award, which can delay or overturn results if the process was not fair.)

- Award and Negotiation: Once the winner is chosen, the agency may conduct final negotiations or clarifications (especially if it’s a negotiated procurement or if discussions were held). Finally, they award the contract. Unsuccessful offerors get notified and have the chance to request a debrief to learn why they lost – something I highly recommend you always do, win or lose, to improve your next proposal.

That’s the official flow, but here are some real-world truths about the RFP process in government:

- Relationships and Communication: Government procurement officials are human. While strict rules prevent any favoritism, good communication and professionalism go a long way. If you submitted questions during the Q&A period, participated in industry day, or otherwise showed engagement, the agency sees that. It can’t win you the contract outright, but it means you’re on their radar. Always be respectful and concise in any communication; contracting folks are busy and often juggling dozens of procurements.

- Behind Schedule Pressure: Often, by the time an RFP is issued, the program is under time pressure. Maybe funding will expire if not obligated by a certain date, or an existing contract is ending soon. This means the evaluators and contracting officer are hustling. If proposals come in huge and bloated (beyond what was asked), that’s actually a negative – evaluators appreciate when a contractor follows instructions exactly and makes their job easier. Clarity and compliance can win over a proposal that is technically brilliant but convoluted or non-compliant.

- Iterative Process: Sometimes an RFP might be canceled and re-issued, or go through amendments extending deadlines or changing requirements. This might happen if industry feedback indicates something was off, or funding changes, or priorities shift. It’s frustrating for contractors, but it happens. Always monitor RFP updates on the official site and respond to amendments quickly.

- Source Selection Sensitivities: The government takes procurement integrity seriously. Evaluators operate in isolation (often each evaluator reads independently before consensus meetings). They do not browse your website during evaluation (they must stick to the proposal). However, they might have some familiarity with your company from prior experience or market research. One reason I emphasize having a strong website and branding (I’ll cover later) is for the market research phase and for when primes or others vet you, not for when the sealed proposals are in review. During evaluation, it’s all about what’s on the page.

In summary, the government RFP process really works like a highly structured competition, but one influenced by preparation and information. The best contractors treat it not as a one-off bid, but as a strategic campaign: they gather intel beforehand, position their team, ensure strict compliance in the proposal, and communicate their value clearly. It’s a ton of work – I often tell clients responding to an RFP is almost like taking on a project in itself, requiring a team (writers, solution architects, pricing experts, editors, etc.) and many hours.

From my perspective, the proposals that win are not just those that meet the requirements on paper, but those that manage to tell a compelling story: Why our team offers the lowest risk and highest reward to the government. The technical volume shows you understand the problem and have a sound approach. The management volume shows you have the right people and quality controls. The past performance shows you’ve done similar things successfully. And the price volume shows you’re offering a fair deal. When all those pieces align, your chances of winning go way up.

We’ll talk soon about specific RFP requirements that decide winners and losers, but one last insight on “how it really works”: the government wants successful outcomes. That seems obvious, but it’s worth remembering. The evaluators and contracting officers aren’t looking to trick anyone or pick an inferior proposal – they genuinely want the best contractor for the job because their mission success depends on it. If you can convince them through your proposal that you understand their mission and will deliver, you’ve already aligned your interests with theirs. It then becomes easier for them to justify choosing you, even if you’re a bit more expensive or less experienced than another bidder, because they see the value. Always keep that mission focus in mind when dealing with the RFP process.

3. RFP Requirements That Decide Winners and Losers

Not all proposal efforts are equal – some proposals come in as clear winners, others are easy cuts. In this section, I want to focus on the specific RFP requirements and factors that often determine who wins and who loses in a federal contract competition.

These are the factors that, in my experience, move the needle most when evaluators score proposals. As a contractor, if you get these right, you dramatically improve your win probability; if you get them wrong, no amount of optimism or relationships will save you.

Let’s break down the key elements:

1. Compliance with Instructions

This one’s non-negotiable: Follow every instruction in the RFP to the letter. Many RFPs include a section (often Section L) with “Instructions to Offerors” and a section (often Section M) with “Evaluation Criteria.” It’s not thrilling reading, but treat it like gospel. If they say 12-point Times New Roman font, you use it. If they say 1-inch margins, do it. If they ask for three past performance examples, don’t give two or five – give three. These might sound trivial, but noncompliance can and will get you disqualified early. Government evaluators often use a compliance matrix to check whether a proposal addressed all requirements and adhered to all instructions. A common RFP mistake is failing to thoroughly review the RFP and overlooking crucial details. Don’t be that contractor.

Tip: Create a compliance matrix for your proposal. This is a checklist (often a spreadsheet) that lists every requirement from the RFP and where in your proposal you respond to it. This ensures nothing falls through the cracks. It’s painstaking, but it’s what separates professional proposal shops from amateurs. Many “losers” in RFPs simply failed to submit what was asked for, in the way it was asked.

2. Understanding of the Requirements

Often an RFP will implicitly or explicitly assess your understanding of the project requirements. If an agency senses you don’t “get” what they need, they’ll be very hesitant to select you. Show that you understand their problem in your own words before proposing a solution. One effective technique is to restate the mission objectives and challenges in the introduction of your technical proposal: e.g., “The Department of X is seeking to modernize its Y system to improve Z – this requires overcoming challenges in A, B, C. We understand how critical it is to [specific outcome].” When I was an evaluator, I often looked for signs of genuine insight – has this company done their homework on the agency’s specific environment? Are they just pasting a generic answer, or do they reference the agency’s mission and constraints? The contractors who demonstrate empathy for the agency’s goals and pain points tend to score higher.

How do you gain that understanding? Research and listening. Read any reference documents provided. Attend the pre-proposal conference or industry day if offered. Ask thoughtful questions during Q&A. Also, research the customer: their strategic plans, recent news, prior contracts. You might uncover hints of what they really care about. An RFP might not spell every detail out, but you can infer priorities by reading between lines. For example, if an RFP mentions “must comply with DOD Instruction XYZ” or “interface with System ABC,” and you know from research that System ABC has some quirks or known issues, addressing that in your approach shows you’re ahead of the curve.

3. Technical Solution & Innovations

The heart of your proposal is the technical approach (or whatever the main delivery approach is for services). This is where you explain how you will do the work. The winner’s proposal usually has a clear, credible, and preferably innovative solution. By innovative I don’t necessarily mean you need to propose cutting-edge tech (unless that’s called for), but you should find ways to differentiate your approach from the competition. Remember, the government will get multiple proposals that all say “we will meet your requirements.” You need to say how in a way that stands out.

Ways to differentiate:

- Present a methodology or framework you use that is proven. For example, “We will execute software sprints using our CMMI Level 3 Agile process, which we have successfully used on similar DoD projects to cut delivery time by 20%.” That specificity and proof can set you apart.

- Address risk proactively. Identify the biggest risks in the project and explain your mitigation plan. This scores points because agencies worry about risk; if you show you’ve thought it through, you seem like a safer bet.

- Include a value-add if you can afford it. Perhaps you offer something beyond the requirements at no extra cost – say, an additional training session, or an improved warranty, or a small innovation the government didn’t explicitly ask for but would appreciate. Make sure any value-add is clearly labeled as “at no additional cost” and is truly aligned to the customer’s goals (no one cares about a free widget that’s unrelated to the mission).

- If the RFP allows, use graphics or tables to make your solution clear. A well-thought-out diagram of your technical solution or project schedule can often convey in one page what 5 pages of text might not. Evaluators love clarity.

Remember that proposals are scored against evaluation factors. If Technical Approach is the highest-weight factor, invest your best minds in that section. If the RFP, for instance, says they will evaluate how well your approach meets the requirements and the feasibility of your schedule, then you must specifically cover those bases: explicitly state how each requirement will be met (maybe with a compliance matrix or crosswalk) and include a credible schedule with key milestones. If you leave something ambiguous (“we will try our best to meet your needs”), that’s weak. If you say, “We will deliver Feature X by Month 3, which meets Requirement Y (per RFP Section C.5) and aligns with the agency’s need to have operational capability by the start of FY quarter 2,” that is much stronger and shows you paid attention.

4. Past Performance and Relevant Experience

We touched on this earlier – Past Performance is often a make-or-break factor. Government evaluators will scrutinize not just what work you did before, but how similar it is to the current project and how well you performed. A frequent scenario: one bidder might have direct experience doing exactly the requested work for a different agency; another bidder might be excellent in general but new to this specific area. The first bidder will usually have an edge if they can prove their success. That’s why, whenever possible, you want to highlight projects that closely mirror the scope, size, and complexity of the RFP at hand.

If you lack direct past performance, you can still play to win by highlighting the experience of your team (key personnel) or partners. The FAR allows considering the past performance of key personnel or subcontractors if relevant. So, for example, if you’re a small business going after a cybersecurity contract but you personally have years of cybersecurity work from a prior job, mention that as a strength of key personnel. Or team with a company that has that past performance (we’ll talk about teaming in the next section too). In your proposal, be explicit: “While [Your Company] is a newer entrant in this domain, our proposed Project Manager led a similar cybersecurity implementation at Department Z with outstanding results. We are also partnering with [Subcontractor] who brings 10 years of experience in X – together, our team has a combined 20 years doing precisely what is required here.”

Don’t assume evaluators will connect the dots – you must clearly connect them yourself. If you have excellent CPARS (Contractor Performance Assessment Reporting System) ratings or award fee scores from previous contracts, mention them (if not precluded by page limits). For example: “Received 100% Exceptional ratings on all six evaluated areas of contract ABC (CPARS, 2023)” – that leaps off the page.

Another tip: Past performance isn’t just about numbers, it’s about narrative. In your past performance write-ups, don’t just list what you did; emphasize outcomes and relevancy. “Developed and delivered new logistics software for Army base Y, completing the project 2 months early and achieving 30% faster processing of supply requests.” Then tie it: “This illustrates our ability to deliver complex IT solutions in a military environment similar to the one required by this RFP, mitigating risk for the government.” You’re effectively saying, we’ve done it successfully before, so trust us to do it again.

One more thing: if you have negative past performance somewhere (maybe a bad CPARS or known issue), there’s a chance the government knows about it (especially if it’s referenced in an official database). Always answer truthfully if asked in the proposal about any issues, and explain what you learned or how you fixed it. It’s better they hear it from you with an explanation than discover it themselves and think you were hiding it.

5. Key Personnel and Team Qualifications

Many RFPs, especially for services, require you to propose Key Personnel – specific roles like Project Manager, Lead Engineer, etc., often with resumes. The government may even dictate minimum qualifications for these roles (e.g., PMP certification, certain years of experience, degree requirements). Having the right people on your team is absolutely a deciding factor. In evaluations, I’ve seen a fantastic technical approach lose because the proposed key staff didn’t meet the qualifications or were clearly under-experienced. On the flip side, I’ve seen agencies essentially choose a team because “they have Joe Smith as the lead and he’s a recognized expert in this field”. That star power or just solid expertise can swing things.

So: never nominate key personnel casually. Make sure they meet all the requirements and then some. Include letters of commitment if required (or even if not required, it shows they are truly on board). If a resume has impressive achievements, consider highlighting or bolding a few that directly tie to the RFP needs (“Led a team of 50 in developing a satellite communication system for USAF – similar in scale to this project”). Ensure your key personnel section answers the mail if there’s an evaluation subfactor for personnel.

Likewise for overall team qualifications: if you are teaming or subcontracting, explain the rationale. The government will evaluate whether your team composition makes sense. If you are a multi-company team, clearly delineate who does what and why that’s the best mix. For example, “We formed a teaming arrangement with XYZ Corp to leverage their unique testing facility for aircraft, a capability few companies possess. This ensures all flight hardware in our proposal will be thoroughly vetted, reducing risk for the Air Force.” That kind of explanation can turn a potential question (“Why two companies?”) into a strength (“Ah, they combined to cover all bases”).

For small businesses: if you’re going after a project that is large, it’s fine to subcontract to larger companies or specialists to shore up capabilities, but be mindful of small business participation rules (many RFPs require a certain % of work by the prime if small, and if you’re small you must do a meaningful portion yourself, often 51%). Also if it’s a small business set-aside, they’ll evaluate your Subcontracting/Teaming Plan to ensure you aren’t just fronting for a big subcontractor. So plan a credible distribution of work.

6. Pricing Strategy

Let’s talk price. Pricing is tricky because it has to be competitive yet sustainable for your business. In an RFP, the lowest price doesn’t always win (unless it’s explicitly LPTA or if all else is equal). The government looks for best value, but you can’t ignore that price is usually a significant factor.

What decides winners/losers in pricing:

- Realism and Consistency: If you underbid unrealistically, agencies might conduct a cost realism analysis and could reject your bid for being too low (if it’s a cost-type contract) or at least score it as high risk. If you overbid significantly, you price yourself out. A good practice is to research what similar contracts have cost (resources like FPDS or usaspending.gov can show you past contract awards) to ensure you’re in the right ballpark. Also, ensure your pricing is consistent with your technical approach – if you promise a huge level of effort or advanced solution but your price budget seems too small to cover it, evaluators will notice the disconnect.

- Transparency: Provide a clear basis of estimate. If the RFP doesn’t require detailed breakdown, giving one anyway (in a cost volume or in an appendix) can help justify your costs. E.g., “Our price of $X is based on Y hours of labor at specified rates, plus materials cost of $Z, etc.” When evaluators see how you built the price, they can judge if it’s reasonable. This can set you apart if others just throw a number and the government is unsure if they understood the scope fully.

- Compliance with Cost Instructions: If the RFP asks for specific pricing tables or uses a government cost model, fill them meticulously. A common mistake is ignoring cost instructions or assumptions provided. For instance, if they say “assume 2,000 hours per year for each full-time person” or “travel costs will be evaluated as offered but not contracted,” follow that exactly.

- Small Business / Socioeconomic Considerations: Some competitions, even full-and-open ones, consider whether you are a small business or have a good Small Business Subcontracting Plan (for large primes). If the RFP requires a plan for how you’ll involve small businesses, that can be a discriminating factor. Likewise, if there are evaluation preferences (like HUBZone price preference where they give a 10% price eval credit to a HUBZone firm), that can effectively decide a winner if it’s a close race. Always highlight if you have a special status or are using one to the government’s benefit (e.g., “As an SDVOSB prime, our proposal meets the agency’s goal of engaging veteran-owned businesses, and we will also subcontract 20% to HUBZone-certified firms, exceeding the solicitation’s requirements.”).

7. Differentiators and Innovation (Bonus Points)

After covering all the basics above, consider what makes your company uniquely suited to this job and make sure that comes across clearly. This could be:

- A proprietary technology or tool you will use.

- Deep prior knowledge of the agency’s environment (perhaps you have former agency personnel on staff – if so, ensure no conflict of interest, but their insight is valuable).

- Exceptional quality processes (CMMI, ISO 9001, CMMC Level 2+ if relevant to cybersecurity, etc. – mention these certifications as they often appear in evaluation as strengths).

- Faster delivery timeline or an ability to surge resources if needed (e.g., you have a pool of cleared candidates ready to hire, which can shorten ramp-up).

- Strong financial stability or existing facilities if that’s relevant (like you already have a cleared facility or secure lab that the project can use from day one).

A word of caution: differentiate on things that matter to the government buyer. Don’t tout a feature that’s irrelevant or marginal. I see this in some losing proposals – they brag about an award they got or a fancy office building, which doesn’t answer the government’s actual needs. Stick to value propositions that align with the customer’s priorities.

8. Presentation Quality

It may seem superficial, but the professionalism of your proposal document itself can sway opinions. This includes:

- Clear organization (use headings and subheadings mirroring the RFP sections so evaluators can easily find where you address each item).

- Clean, typo-free writing. Grammar or spelling mistakes, or copious jargon and buzzwords without explanation, can hurt credibility. An evaluator might think, “If they can’t proofread or communicate clearly, how will they perform the contract?” I always recommend having a fresh set of eyes do a red-team review of your proposal before submission to catch errors and unclear text.

- Consistent formatting. Use the same terminology throughout. If your team name is “Acme Team,” don’t elsewhere call it “Team Acme Solutions” – little inconsistencies can confuse. And ensure any graphics are legible (sometimes we get proposals with images or org charts that are too small or blurry to read – that frustrates evaluators).

- Compliance and responsiveness aside, make it easy for the government to evaluate you. If you can, literally map your proposal sections to the evaluation criteria. Some bidders even label sections like “Factor 1: Technical Approach – [Offeror Name]” etc., so there’s no doubt. Also, if the RFP had a checklist or outline they expected, follow that structure.

9. Q&A and Amendments

Keep an eye on the Q&A responses the government issues and any RFP amendments. Sometimes an amendment will add a requirement or change a due date – failing to acknowledge an amendment can be fatal. Or Q&A might clarify something that you need to address. I’ve seen losing proposals that clearly didn’t account for a Q&A answer (maybe they wrote their draft early and missed that the government said “By the way, all solutions must use XYZ standard,” and they didn’t incorporate that). Staying updated is crucial. Incorporate any changes into your final submission and, if required, sign/acknowledge all amendments.

10. The Offeror’s Overall Credibility

Finally, beyond all the specifics, there’s a somewhat intangible factor of credibility that comes from the sum of all parts. A proposal that checks all the boxes, provides a strong solution, a reasonable price, and has a confident tone (not arrogant, but confident) will leave evaluators with the impression, “This company can do the job, and we won’t regret picking them.” Conversely, a proposal with unanswered questions, vague claims, or too much fluff will sow doubt.

Credibility is reinforced by things like: citing relevant standards, including data or metrics from past successes, demonstrating knowledge of regulations (e.g., you mention compliance with Section 508 accessibility or FAR clauses where appropriate, showing you are not new to federal requirements). If the RFP is for the Department of Defense, for example, and requires certain security clearances or compliance with CMMC (Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification), explicitly stating your status (“We are CMMC Level 2 certified as of 2024, and our team includes cleared personnel up to Top Secret level”) removes uncertainty and scores points.

One more note on differentiators: In this era, being a multi-industry contractor can be a differentiator if presented right. For instance, if you’re a defense contractor with significant commercial tech experience, you can spin that as “We bring cutting-edge commercial innovation to our government customers, not just traditional approaches.” Government buyers do appreciate innovation when it’s relevant. In fact, an interesting trend: many defense agencies are looking to non-traditional vendors (startups, commercial firms) for new solutions. If you have that kind of multi-industry DNA, highlight the synergy (e.g., “Our experience in the automotive industry electrification will directly benefit this military vehicle project by applying proven EV technologies.”)

To sum up this section: winners pay attention to compliance, understanding, technical excellence, credible past performance, strong team, fair pricing, and clear differentiators. Losers often slip on one or more of those – maybe they missed a requirement, or their price was out of whack, or they just didn’t convince the government they understood the problem. The good news is, all these things are within your control as a bidder. Yes, competition can be tough, but by focusing on these key requirements, you put your best foot forward.

Actionable Takeaway: Before submitting any proposal, do a rigorous final check: put yourself in the evaluator’s shoes with the RFP criteria in hand. Score your own proposal. Did you answer every requirement? Did you make it easy to find each answer? Are your strongest selling points clearly stated (not buried)? Did you eliminate generic fluff and tailor everything to the client? This self-evaluation can highlight last-minute fixes that turn a mediocre proposal into a winning one.

Next, we’ll take a step back and look at the RFP contract lifecycle – understanding not just the proposal phase, but the whole journey of a contract from cradle to grave, because savvy contractors plan for the long game.

4. Understanding the RFP Contract Lifecycle

Winning an RFP is not the end – it’s just one milestone in the broader contract lifecycle. Understanding this lifecycle is crucial because it helps contractors anticipate next steps, manage ongoing obligations, and even position themselves for future opportunities. In this section, I’ll break down the key phases of a government RFP contract’s lifecycle, from pre-solicitation all the way to contract closeout (and re-compete). By grasping this, you can not only strategize to win contracts but also execute them successfully and leverage them for long-term growth.

Here’s an overview of the typical lifecycle of a federal contract initiated by an RFP:

1. Pre-Solicitation (Planning & Market Research):

Before an RFP is released, the government goes through need identification and market research. The agency defines its requirements and determines acquisition strategy (Will it be full and open? Small business set-aside? Use an existing contract vehicle?). Often, they’ll post Sources Sought notices or draft RFPs to gather input. As a contractor, this is your time to position yourself. Engage with small business offices, attend industry days, maybe even influence the RFP if an agency is open to suggestions. This phase sets the stage for what kind of RFP comes out. If you’re tracking an opportunity early (say through agency forecasts or relationships), you can prepare in advance – lining up partners, getting certified (if it becomes a set-aside, e.g., an 8(a) or SDVOSB opportunity), or even helping shape the requirements through white papers or responses to RFIs.

From the agency side, this phase is about aligning the project with budgets and ensuring they understand the marketplace offerings. It’s also where they decide the type of solicitation – RFP vs. RFQ vs. OTA (Other Transaction Authority) or something. Defense agencies might consider whether to use an IDIQ or GWAC (Government-Wide Acquisition Contract) instead of an open RFP. So, if you’re not on those vehicles, you might miss out (more on contract vehicles in a moment). But assuming it’s an open RFP, we proceed to solicitation.

2. Solicitation (RFP Issuance):

The agency formally issues the RFP (often on SAM.gov for federal contracts over $25k). This is the go live moment for competition. The RFP will include a schedule – typically with dates for a pre-proposal conference, Q&A deadline, and proposal due date. Sometimes they allow a draft review or multiple Q&A rounds if it’s large. The clock is ticking for contractors to craft their proposals.

During solicitation, the agency may interact through posted Q&As to clarify the RFP. They might also issue amendments (say to extend the deadline or fix errors in the RFP).

Internally, the agency is often setting up its evaluation team at this point – identifying who will be the evaluators, securing necessary approvals, etc. There can also be a period (after proposals are in) if they decide to have “discussions” or allow final proposal revisions (common in negotiated procurements if no one hit the mark perfectly and they want to give a chance to improve). But often in best-value RFPs, they aim to award without discussions if a clear winner emerges.

For contractors, this is the heavy lift proposal phase we discussed in earlier sections. It’s all hands on deck to produce a compliant, compelling proposal by the deadline. Some companies have dedicated proposal managers and teams working long hours, possibly using proposal development frameworks (like Shipley process, which many GovCon firms follow for proposal planning).

3. Evaluation & Award:

After the submission deadline, the agency’s evaluation process kicks in (this we detailed in “How it really works”). They may do evaluations in phases (technical screening, competitive range determination, etc.). Eventually, they make a source selection and an award decision is documented. The contracting officer signs a contract with the winning vendor (or multiple winners if it’s a multi-award scenario).

At this point, losing bidders are notified. They usually get a brief notice indicating who won and (in some cases) the price, but not a full explanation. They have the option to request a debriefing – and I always advise to request it, because you learn how your proposal scored and why you lost or won, which is invaluable feedback. Also, the clock for any protest generally starts after debriefing. Some contractors will file a protest if they believe something was unfair in the process. Protests (to GAO or to the agency) can delay the award. It’s worth noting that if you win, a protest can put your contract on hold for months while it’s resolved. As a winner, you typically have to wait until protests are cleared to start work (unless it’s an override for urgent need, which is rare). As a loser, you might protest if you have strong reason (like you suspect the eval overlooked something or the winner was ineligible, etc.), but protests are a tool to use with caution – they can sour relationships if done frivolously. In my view, only protest if there’s clear evidence of an error or unfairness.

Assuming no protest (or once resolved), the award is finalized. You now have a contract – congrats! What next?

4. Kickoff & Transition:

Many contracts, particularly service contracts, start with a kickoff meeting or a transition period. If there was an incumbent, you might have to transition from them (taking over staff, knowledge transfer, etc.). If it’s new work, you’ll set up initial meetings with the Contracting Officer (CO) and Contracting Officer’s Representative (COR) to align on expectations, reporting, etc. This phase is critical: first impressions matter. The government will watch whether you hit the ground running or stumble. I always aim to deliver some quick wins in the first 30-60 days – it sets a positive tone.

For project-type contracts, you might have to provide a project management plan or updated schedule 30 days in. If it’s product delivery, perhaps initial design reviews. Make sure you meet any early deliverables and deadlines. If security clearances or facility access are needed, those processes start ASAP since they can take time.

Internally, you’ll want to ensure your team is ready: hire or reassign staff, get any subcontracts in place (with your partners that were on the proposal), set up accounting to track this contract’s costs (especially important if it’s cost-reimbursable – you’ll need a DCAA-compliant accounting system, etc.). The execution phase is where all those promises in the proposal have to be turned into action.

5. Contract Performance & Management:

This is the longest phase – doing the work. It could be years of effort with ongoing deliverables, services, or development milestones. Contract management involves fulfilling the scope, managing your resources, and maintaining compliance with all contract clauses and government regulations.

A few things to keep front-of-mind during execution:

- Communication with the customer: Regular status reports, meetings, and informal check-ins are vital. If something is going off-track, raise it early with a plan to fix it. Government clients do not like surprises. Remember, they want you to succeed once they’ve picked you (failure is headache for them), so keep them informed and often they will work with you on solutions (e.g., adjusting a requirement or timeline if reasonable).

- Quality and Compliance: Deliver what you promised, at the quality you promised. If the contract has specific metrics (uptime, response time, deliverable acceptance criteria), track them internally and ensure you’re meeting or exceeding them. Also comply with all the contract clauses – for instance, many DoD contracts now include cybersecurity clauses (you might have to maintain a certain security posture). Or labor laws (if it’s subject to Service Contract Act, you must pay certain wages). This is where a good contracts manager or project manager on your side pays dividends to keep everything in check.

- Documentation: Keep records of everything – delivered reports, sign-offs, emails of scope clarifications – because if staff change or disputes arise, documentation protects you. Also, if modifications to the contract happen (they often do, via formal contract modifications to add scope, cut scope, extend time, etc.), handle them formally through the CO. Don’t proceed on just verbal directions if it affects cost or schedule; politely ask for confirmation in writing or a contract mod. This avoids payment issues later.

- Financial management: Make sure you invoice correctly as per the contract terms (some are monthly, some milestone-based). Federal invoicing might be through systems like WAWF (Wide Area Workflow) for DoD or others. A common challenge for new contractors is cash flow – the government can pay slow, perhaps 30 days or more after invoice. If you’re a small business, take advantage of any prompt pay policies (there’s an initiative for accelerated payments to small biz primes). Still, be prepared with a line of credit or reserves because executing a contract means fronting payroll and expenses before reimbursement. I’ve experienced those pains – waiting 60+ days for first payments – plan for it.

Performance is also where Past Performance is earned. The agency will likely do interim and final evaluations (CPARS entries). Aim for excellent ratings by exceeding expectations. Good performance not only secures the current work (they might give you more tasks or options), but it’s your ticket to win future RFPs (you’ll use these successes as references).

6. Contract Monitoring and Modifications:

During performance, the contract might evolve. There could be option years – government contracts often are awarded base year + option years (especially service contracts). The government usually must actively decide to exercise each option. If you’re performing well, options get exercised and you continue seamlessly into the next year. If not, they might not renew. So treat each year like a re-earning of the client’s trust.

Sometimes scope changes – maybe the agency’s needs shift or budgets change. They might negotiate a modification to add work (or cut work). If they add, ensure to negotiate equitable adjustments (you should get paid for added scope). If cut, they might de-scope and reduce funding. Stay flexible and cooperative but also protect your company’s interests through proper contract mods for changes.

7. Contract Closeout:

All contracts eventually end. Closeout is a formal phase where all obligations are wrapped up. You submit final deliverables, final invoices, the government makes final payments, property is returned if any (like government-furnished equipment), and administrative paperwork is completed (release of claims, etc.). On the government side, they’ll ensure all deliverables were received and that you don’t owe them anything (like unspent advance payments, etc.). They’ll also finalize your performance evaluation.

For many service contracts, closeout is straightforward – final invoice and a performance review. For complex project contracts, there might be final acceptance testing or audits. If it’s a cost-type contract, contract auditors might audit your incurred costs before settling final payment. Keep your records tidy for this eventual audit.

Closeout can take a while (I’ve had closeouts linger due to audits for a couple of years after work completion). But from a contractor perspective, you should push to close out so you can free up any held funds (e.g., they might hold some retainage).

8. Re-compete and Next Opportunity:

Now, smart contractors think ahead: if this work is ongoing in nature, the government will likely re-compete it when the contract term ends (unless it’s a one-time project). Many contracts have a 3-5 year span, after which a new RFP will be issued for the follow-on. This is where incumbency is an advantage but not a guarantee. As the incumbent contractor, you should be constantly positioning to win the re-compete. That means continuing to deliver excellent service, keeping the customer happy, and innovating during the contract so that by the time of re-compete, you have a strong case that “we’re already doing a great job, why change horses?”

However, also watch for complacency – I mentioned earlier how some incumbents lose because they assume retention. Always treat re-competes like a fresh competition, because often your competitors are eyeing that contract and perhaps talking to the customer’s stakeholders too, highlighting any little dissatisfaction. It’s a tough game – you basically have to do well and still write a superb proposal to keep it. One strategy is to keep track of your contract’s outcomes and metrics over its life, so you can cite them in the next proposal (“Under our tenure as incumbent, downtime was reduced by 30%, user satisfaction scores improved to 4.8/5, etc.”). Turn your performance into data points.

For companies who lost this contract originally, they might try again on re-compete. I’ve seen scenarios where an incumbent did fine, but a new competitor came in with a much lower price or a new approach and won. Government likes stability but also has pressure to use competition to get better deals. So always be ready to defend or capture a contract at re-compete time.

9. Lessons Learned & Relationship Building:

Between contracts, or even during, take time to gather lessons learned. Do an internal post-mortem on your proposal process (what can we do better next time?), and on execution (what did we excel at, where did we stumble, what feedback did the client give?). This continuous improvement mindset is key to growing as a government contractor. Many successful defense contractors have institutionalized capture and proposal processes that refine with each pursuit.

Also, maintain the relationship with your government customer beyond the contract. If you performed well, they are a reference for you and might want you in other projects. Keep them informed of your new capabilities or offerings (lightly, without spamming – maybe through occasional newsletters or capability statements). Even if key people move to other agencies, that’s an opportunity – they might bring you into a new circle if they were impressed with your work.

Understanding the contract lifecycle also means recognizing that sometimes strategies like “getting a foot in the door” can pay off. For example, you might take a small contract or a subcontract now to build past performance and relationships, leading to a prime contract later. Or you may accept a tougher contract (low margin) just to prove yourself in a new market, with the goal of leveraging that success to win more lucrative work subsequently. This long-term view separates those who chase one-off wins from those who build a sustainable contracting business.

In summary, the RFP contract lifecycle spans from initial planning to final closeout and re-compete. At each phase, there are actions you can take to increase success:

- Early positioning before the RFP (so you shape it rather than react to it).

- Crafting a winning proposal during solicitation.

- Delivering excellence during execution (so you get good past performance and maybe contract extensions).

- Preparing for re-compete or other opportunities using the experience gained.

Keep this lifecycle in mind as you allocate resources. For example, some firms spend so much on proposals but then under-resource the project management during execution – that’s counterproductive; you win but then could falter in delivery. Balance your investments across capture (pre-RFP), proposal development, and project execution, because they all feed each other. Execution success gives you an edge for the next capture, and so on.

Lifecycle Quick Reference (for your team): Consider creating an internal checklist or flowchart of the contract lifecycle. At HILARTECH, we advise having a “Contract Lifecycle Checklist” for each major contract, covering:

- Pre-RFP: actions taken (customer contacts, research done, team ready).

- Proposal: compliance check, red-team review completed, submission confirmed.

- Post-Award: kickoff held, all start-up actions done (staff hired, systems set).

- Ongoing: monthly/quarterly reviews of performance vs. contract requirements.

- Pre-Close: archive project docs, seek CPARS review meeting, prep re-compete capture plan 1 year out from end.

Such a checklist ensures you don’t drop the ball at any stage and is a tool you can refine over time.

Now that we’ve looked at the full lifecycle, let’s zoom out and consider where these RFPs come from – specifically, where government buyers find defense contractors to invite or to consider for their needs. Understanding how and where agencies search for contractors will help you be visible in the right places.

5. Where Government Buyers Find U.S. Defense Contractors

How do government agencies actually find contractors, especially in the vast U.S. defense sector? Knowing this is critical for business development, if you’re not findable where they’re looking, you’re missing opportunities.

Government buyers (contracting officers, program managers, and their market research analysts) use several channels to identify potential vendors. Some are formal databases, others are through networking and events, and increasingly, digital presence (including search engines and AI-driven tools) plays a role. Let’s break down the main avenues:

SAM.gov and Official Contract Databases

SAM.gov (System for Award Management) is the primary portal for federal contract opportunities and the primary database of registered contractors. By regulation, federal agencies must publicize most contract solicitations over $25,000 on SAM (formerly known as FedBizOpps/FBO). But beyond finding current opportunities, agencies also use SAM.gov to search for vendors. SAM has a search function that lets you find companies by keywords, NAICS codes (industry codes), small-business categories, and more. Contracting officers often do this to create a list of possible vendors when starting an acquisition.

What this means for you: Your SAM.gov registration and profile needs to be complete and optimized. Make sure your NAICS codes (North American Industry Classification System codes) cover all the work you can do – but also don’t spam every code under the sun; focus on your core competencies so you show up as relevant. Include detailed capability narratives in your SAM profile. SAM includes an area for a “Capabilities Narrative” and links to the SBA’s Dynamic Small Business Search (DSBS), where you can enter past performance, keywords, and other details. Government buyers do use these fields. In fact, as noted in a DoD guide, “You can identify potential buyers of your services by searching SAM.gov… sort data by NAICS, keyword, customer, etc.” – the same works in reverse; buyers find sellers.

For small businesses, the Dynamic Small Business Search (DSBS) is a tool often used by agency Small Business Specialists. It’s fed by your SAM data and additional fields. If you’re, say, an SDVOSB specializing in cybersecurity, an agency wanting SDVOSBs for a certain project might search DSBS for “cybersecurity SDVOSB” in their state, etc. Make sure those keywords are in your profile. A common mistake is leaving generic descriptions or not listing your differentiators there. Use that space to say exactly what problems you solve or technologies you excel in.

Other databases: If you’re on certain government contract vehicles or schedules, there are associated databases. For example, if you have a GSA Schedule, your info is in GSA eLibrary and GSA Advantage, and agencies frequently search those for available schedule contractors. Likewise, if you’re part of a Government-Wide Acquisition Contract (GWAC) like NASA SEWP, there’s a repository of contractors the buyers on those GWACs use. The DoD also has tools like DOD SBIR/STTR company databases for innovative tech firms, and the FedMall for certain product purchasing. But SAM.gov is the big one for broad market.

Additionally, agencies use FPDS (Federal Procurement Data System) and USAspending.gov to see who has won contracts in specific areas (who buys what from whom). If, for instance, an Air Force base needs a new IT support vendor, they might look up which companies have done IT support for similar bases or commands via FPDS. That historical data can surface your company if you’ve done relevant work. You can’t directly edit FPDS (it’s automatically recorded from contract awards), but just be aware your track record is visible. Some savvy agencies and definitely prime contractors use commercial tools like Deltek GovWin, Bloom Government (now Euna), etc., which aggregate this data for market intel. Being active and successful in the market begets more visibility in these channels.

Industry Outreach: RFIs, Industry Days, and Conferences

Government buyers often find contractors through outreach events. An Industry Day is a meeting (sometimes virtual now) where an agency’s procurement team briefs industry on a forthcoming RFP. It’s both an info-sharing and a scouting exercise – they see who’s interested and you learn more about the opportunity. Attending industry days (and asking smart questions there) can put you on the radar. I’ve had agency folks remember, “Oh yeah, Company X asked that insightful question at Industry Day – they seem to know their stuff.”

Similarly, responding to RFIs (Request for Information) and Sources Sought notices is vital. Some companies skip these because they consider it speculative effort, but responding can significantly improve your chances. The government takes note of responders; plus, as mentioned earlier, it lets you shape the requirements or at least be prepared for them. Sometimes RFIs explicitly request capability statements or questions about how you’d approach a task. Those responses could later be read by the team drafting the RFP (I’ve been in meetings where we reviewed RFI responses to decide the scope or set-aside status of a solicitation). So this is a chance to “advertise” your capabilities directly to the customer in the context of their need.

Conferences and Trade Shows: Defense agencies and units often participate in industry conferences (like those by NDIA, AFCEA, AUSA, etc.). Program managers and acquisition folks attend, give briefings, and meet vendors. These events are networking goldmines. Government attendees might not openly advertise that they’re seeking contractors, but trust me, they are observing and collecting information. If you have a booth, give a talk, or network well, you might be remembered when an RFP comes up. For example, a Navy program officer might meet a small tech company at a Navy League symposium and later ensure that the company hears about a relevant upcoming project or includes them in market research outreach. It’s indirect, but it happens often.

There are also matchmaking events hosted by agencies (especially geared to small businesses). The SBA and agency OSDBUs (Office of Small & Disadvantaged Business Utilization) organize events where small businesses can do brief capability pitches to agency reps or primes. These are good for making initial contacts. The result might be being added to a distro list for future notices or even invited to bid on smaller opportunities.

One note: certain defense agencies cannot just single-source to someone they met at a conference (unless you have something unique like a patent, or qualify for a sole source via 8(a) or SDVOSB in some cases). But being known to them means you might get included in RFPs that have limited distribution (some RFPs under certain thresholds or specific to contract vehicles aren’t public on SAM – they might just go to a few pre-selected vendors). Or at minimum, when your proposal comes in, they mentally connect it to a face and positive impression.

Prime Contractors and Teaming Networks

Government buyers also “find” contractors indirectly through prime contractors. In large defense programs, big primes often have outreach to find subcontractors or niche capabilities. For example, if Lockheed Martin or Boeing is bidding a huge system and they need a small business partner for a piece, they might reach out in their network or post a partnering opportunity. Sometimes agencies even facilitate “industry matchmaking” especially for set-aside components (e.g., the Air Force might hold an event where large primes meet small businesses for an upcoming multi-billion program with small business goals).

If you’re a small or mid-size firm, connecting with larger integrators can get you visibility. They might bring you on to fulfill subcontractor requirements or because you have a specialized product. How do you connect? Attend those industry days (primes are there too), join industry associations, and utilize platforms like DoD Mentor-Protégé Program or SBA’s Mentor-Protégé which often pair smalls with bigs. Primes also browse the same SAM and DSBS databases when seeking specific types of partners (I’ve had large primes call me because they found our profile as an SDVOSB in a specific NAICS and needed to round out a team).

Also, LinkedIn and professional networks have become surprisingly useful. Many contracting officers and program folks lurk on LinkedIn (some post about what they need or upcoming events). Being active in GovCon discussions and showcasing your expertise can catch a notice. I once got a message from a government IT PM who saw a post I made about a certain technology; they asked if our company does contracting in that area because they had a need. This didn’t directly result in a contract (they still had to do an RFP), but it allowed us to position early.

Procurement Forecasts and Portals

Agencies often publish procurement forecasts – basically, lists of planned upcoming solicitations, especially aimed at small businesses. For example, the Department of Defense, Homeland Security, etc., have websites or PDF docs forecasting what they intend to bid out in the coming year or two. These forecasts typically list a short description, an anticipated value, whether it might be a set-aside, and a point of contact. Government buyers assume interested businesses will read those and reach out to the point of contact or be ready for when it drops. I monitor these to know where to target our marketing.

Some agencies have their own vendor portals or registration systems. For instance, the Army Corps of Engineers has an internal database, and some Air Force bases require contractors to register in their Vendor Communication system. While SAM is universal, don’t ignore specific agency portals if your target customer uses one. NASA has an NSRS (NASA Supplier Registration System) for its centers. Checking agency websites for a “Doing Business With…” page will usually reveal whether they have a unique process for vendors to get on their radar.

Local and Regional Networks

Many defense contractors cluster around major installations or regions (Washington DC/Northern Virginia, Huntsville AL, San Diego, etc.). In these hubs, local networking can be powerful. Government personnel might speak at local tech council meetings or base-related commerce events. Being engaged in the local defense community means word-of-mouth can spread. Contracting officers might ask a trusted colleague, “Do you know any company that does X?” and someone might refer them to you if you’ve made a good impression in the community.

Also, some state and local government offices maintain lists of defense contractors (economic development agencies love to showcase companies in their region doing federal work). Florida, for example, where our firm is, has organizations that connect and promote defense businesses. These aren’t direct pipelines, but they contribute to an ecosystem where buyers and sellers are more likely to cross paths.

The Role of Digital Presence (Websites and Search Engines)

This is near and dear to me as a web design professional: your online presence can absolutely influence whether government buyers find you.

Consider how people in general find information today – they Google it (or use other search engines, even the new AI chat-based searches).

Contracting officers and program staff do that too for market research. They might search “XYZ capability small business” or check if a company they heard of has a legitimate website. A poor or nonexistent web presence can make you effectively invisible or raise doubt about your credibility.

We have numerous examples where a client’s revamped website led to increased inquiries from agencies and primes. One reason is search engine optimization (SEO) and what I call Answer Engine Optimization (AEO). For instance, if you specialize in “radar signal processing” and you publish a white paper or case study about it on your site, a government researcher searching that term might land on your page and discover your company. It’s happened to me: our site’s articles on federal contracting get hits from government domains, meaning folks at agencies are reading them. If you have content that answers their questions (like “How to achieve CMMC Level 2 compliance” – if an agency person is curious which vendors know CMMC, your content could attract them), you gain mindshare.

Furthermore, schema markup on your site (structured data, such as FAQ schema) can enhance how your information appears in search results, potentially making it easier for AI-based search to extract details. This is a bit advanced, but adding FAQ sections on your site about your services or government contracting topics can position you as an authority. Google’s algorithms notice that. I ensure clients implement things like FAQ schema and Article schema on key pages, so when someone searches a question like “SDVOSB web design agency for government contracts,” if we have an FAQ “What is a SDVOSB and why choose one for federal web design?” it might show up prominently. It’s about being discoverable and answering the questions buyers might ask.

Linked Data and Directories: In addition to your website, make sure your business is listed in relevant directories: the DoD’s small business office directory (if they have a listing of vendors by category), any industry association directories, and of course maintain your LinkedIn page. Government folks do look at LinkedIn profiles of company execs to gauge size and legitimacy. If you claim to be a 500-person company but LinkedIn shows 5 employees, that’s a red flag.

Finally, note that certain specialized acquisition areas have their own “marketplaces.” For example, the DoD’s Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) has a portal where companies can submit solutions to problems, and SOCOM has SOFWERX for special operations tech collaboration. These aren’t exactly RFPs but ways to get noticed for innovative stuff.

In summary, government buyers find defense contractors by:

- Searching official databases like SAM.gov and DSBS – hence, optimize your registrations.

- Engaging through RFIs and industry events, so be present and responsive.

- Leveraging primes and teaming – network with larger contractors and industry partners.

- Using procurement forecasts and local networks – stay plugged in to those.

- Looking online – ensure your website and digital content speak to what you do in the language the government understands.

A quick personal anecdote: I once asked a contracting officer during a debrief, “Out of curiosity, how did you first hear about us?” The answer: “I saw your company mentioned in an industry presentation at a conference a year ago, and I remembered the name when your proposal came in. Also I checked your website during market research and it looked like you specialize in exactly what we needed.” That reinforced to me that everything we do to be visible and credible – from conferences to our website content – contributes to being found by the right buyers. It’s not just luck.

Internal Link Suggestion: For readers interested in enhancing visibility, see our guide on “Federal Procurement Process & Importance of Web Presence”, which dives deeper into how each stage of procurement can be supported by a strong website. Also, consider downloading our GovCon Marketing Checklist (free tool) to ensure you’re covering all channels where agencies might be searching for you.

Next, we’ll explore a topic we touched on earlier: multi-industry defense contractors – what does that mean, and why does it matter in this competitive marketplace?

6. Multi-Industry Defense Contractors and Why They Matter

The term “multi-industry defense contractors” may sound like a buzzword, but it captures an important trend in government contracting: the most successful defense contractors often operate across multiple industries or sectors, bringing a combination of capabilities. In a multi-industry marketplace – where a single project may require expertise in aerospace, software, and cybersecurity simultaneously – the ability to operate across those domains is a significant advantage. Let’s unpack why multi-industry capability matters and how contractors can leverage it.

What Does Multi-Industry Mean in Defense?

Traditionally, defense contracting was segmented – you had pure-play companies in shipbuilding, or in IT, or in logistics. Now there’s increasing overlap. For example:

- A company building military drones (aerospace industry) also needs to excel in AI and data analytics (software industry) for autonomous functions, and in telecommunications (to control the drone and relay intel). So a drone contractor might branch into software development and satellite communications.

- A cybersecurity firm working with the DoD might also venture into cloud computing and hardware encryption devices (tech industry meets electronics).

- Even at the big end: Companies like Lockheed Martin or Boeing are not just making jets; they have divisions for IT, space systems, and services. They’re inherently multi-industry conglomerates.

For smaller contractors, multi-industry often means you have a blend of skill sets and certifications. Perhaps you started in defense healthcare consulting but also developed a cybersecurity practice, making you relevant to two types of RFPs (health IT and cyber). Or you’re a construction firm that also specializes in installing advanced security systems, merging construction with technology.

Dual-use technologies are a big part of this – where something has both military and civilian applications. If you develop a technology that can serve commercial markets and defense, you’re by default multi-industry. Many innovative companies (think of those in robotics, AI, biotech) find themselves contracting with DOD while also selling commercially.

Why Being Multi-Industry Matters to Government Buyers

- Comprehensive Solutions: Government problems are rarely siloed. If the Army has a problem of securing bases, the solution might involve physical security (fences, sensors), cyber (network protection), and personnel training. A multi-industry contractor can offer a more integrated solution than the government coordinating multiple niche vendors. This can reduce risk and administrative burden for the agency. I’ve seen RFPs favor teams that demonstrate “multi-disciplinary” strengths because mission requirements span multiple areas.

- Innovation and Best Practices: Cross-industry collaboration can drive innovation. A contractor with commercial experience in, say, agile software development might apply that to defense systems that historically used slower waterfall models, thus delivering faster. Or a firm that worked in automotive manufacturing could bring lean processes to military vehicle production. Forbes observed that defense contractors are increasingly diversifying outside traditional markets, which can introduce fresh perspectives and technology to defense programs. Government buyers value this when it leads to better performance or cost savings. One DoD initiative for innovation is specifically to attract non-traditional, diversified companies to bring new solutions (because purely defense-focused companies might be set in certain ways).

- Stability and Resilience: From the government’s standpoint, a contractor with multiple industry bases may be more financially stable and resilient. If one sector’s spending is down (say DoD budgets dip), the company isn’t going bankrupt; they have other revenue streams. This reduces the risk of contractor default or financial problems during the contract. It’s not usually an official evaluation factor, but agencies do consider a vendor’s health informally. Multi-industry players often weather economic cycles better. (During the sequestration in 2013, for instance, companies that also had commercial business were less impacted than those solely reliant on federal dollars.)

- Multi-Domain Operations: The military itself is pursuing multi-domain operations (integrating land, air, sea, space, cyber). They’ll need contractors who can operate and connect tech across those domains. Being in multi-industry positions positions a contractor to be a partner in these comprehensive initiatives. It’s one reason you see a lot of mergers and teaming lately – companies are trying to present a broader front to tackle complex programs (like JADC2 – Joint All-Domain Command and Control – which requires communications, software, hardware integration, AI, etc., no single traditional contractor covers all of that well).

- Meeting Diverse Procurement Goals: An agency may bundle different types of work into a single RFP to improve efficiency. If you are multi-capable, you can bid as prime on a bundled contract rather than seeing it go to someone else. Also, if a program has multiple segments (some R&D, some production, some training), being able to fulfill more than one segment makes you more attractive as a one-stop-shop. Government likes not having to manage an army of contractors if one or a few can do it all.

Why It Matters for Contractors (Competitive Edge)

From the contractor perspective, being multi-industry opens more doors. You can chase a wider range of RFPs and you can differentiate your proposals by highlighting that breadth:

- If competition is all software companies, but you’re a software + hardware company, you might pitch that “We not only develop the system, we can also build the custom hardware it runs on, ensuring seamless integration and accountability under one roof.”

- If others provide service and maintenance after deployment by outsourcing, but you have an in-house service division, you can emphasize that continuity.

However, there’s a balance. Multi-industry doesn’t mean jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none. You still need depth in each area you claim. Government evaluators will see through it if you just list a bunch of capabilities but have no strong past performance or talent in them. So typically, companies grow multi-industry by acquiring or partnering with specialists, or developing separate divisions with distinct expertise. If you’re not truly strong in something, better to partner than to pretend.

Examples of Multi-Industry Synergy